Written by possibly the most influential libertarian of our generation, Liberty Defined is a must read book. In this collection of essays, Ron Paul lays out a libertarian philosophy on 50 topical issues, arranged in alphabetical order from “Abortion” to “Zionism”. It is a book that can be read in any order you like. But no matter where you start to read, you have to read more.

‘We need intellectual leaders’ said Austrian economist F.A. Hayek, ‘who are prepared to resist the blandishments of power and influence and who are willing to work for an ideal, however small may be the prospects of its early realization'.[1] Such intellectual leaders are hard to find!

A former obstetrician, Ron Paul is a Congressman from Texas and a candidate for the Republican presidential nomination in 2008 and 2012. But nowhere in his book does Paul take even the slightest opportunity to indulge in electioneering or political posturing. Every line and chapter would be equally as potent whether Ron Paul ran for presidential office or not. Nowhere does he say that he is the solution to a problem, if only people would vote for him. At its heart, the book is not about policy prescriptions at all; it is the opposite to the usual political message. It’s about pulling back the proverbial curtain and revealing political schemes and wizardry as being inept and, more often than not, counterproductive. It does this forthrightly, bravely and uncompromisingly – and not just ‘for a politician’ but for anybody.

Ron Paul uses each of the 50 mini essays to hack away at the thick ivy of mystique surrounding government regulations, taxes, programs and schemes. He takes every opportunity to show that governments are the cause, not the solution, to human problems – whether they are related to ‘Slavery’ or ‘Education’ or any other area of concern. The legendary libertarian writer Murray N. Rothbard implores that “the libertarian must never allow himself to be trapped into any sort of proposal for ‘positive’ governmental action; in his perspective, the role of government should only be to remove itself from all spheres of society just as rapidly as it can be pressured to do so".[2]

In these 50 short chapters, nothing is spared from the microscope and the axe, not even the notion of ‘democracy’:

As much as I defend the freedoms of everyone, those freedoms should be limited in the following sense: People should not be able to vote to take away the rights of others. And yet this is what the slogan democracy has come to mean domestically. It does not mean that the people prevail over the government; it means that the government prevails over the people by claiming the blessing of mass opinion. This form of government has no limit. Tyranny is not ruled out. Nothing is ruled out.

When it comes to foreign policy and trade policy for example, such a society would practice, as Thomas Jefferson famously said, ‘Peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations — entangling alliances with none’. He says ‘sanctions and blockades are dangerous and should be considered acts of war’.

A free society would have no place for ‘prohibition’. Paul draws parallels between the various government enforced prohibitions of today, and the havoc wreaked by alcohol prohibition in the 1920s, which bred lawlessness, underworld criminal syndicates, violence and poor quality products that endangered users. Under prohibition all honest people must surrender some of their freedom to the busybody inspectors who want to police the behaviour of others in a misguided effort to correct their habits.

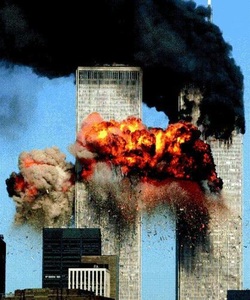

Ron Paul minces no words in calling modern day America a ‘military client-run empire’ which he compares to the Roman Empire of old or the British colonial empire of recent history. With 900 military bases housing US troops in 135 countries, he says ‘Truly, the United States is an empire by any definition, and quite possibly the most aggressive, extended, and expansionist in the history of the world. Do we really find it shocking that some people in the world don’t like this?’ This empire, consuming the lives of American soldiers and the wealth of future generations, is the ‘enemy of American freedom’.

The chapter on unions is particularly well written, and this crude summary may not do it justice. Paul defends the right of people to form groups and to negotiate collectively. But he strongly opposes the use of violence and force against others, and any union powers gained by legislation he puts in this category. Often, big labour, big business and big government combine to enrich themselves at the expense of others. He goes on to show how ‘when the goal is liberty, prosperity flourishes and is well distributed. When economic equality is the goal, poverty results’.

Ron Paul writes to an American audience that is often deeply divided between conservative and progressive, religious and secular, etc. Yet none of these rifts pose any problem to the liberty based society Ron Paul envisions. In the chapter entitled ‘Evolution Versus Creation’ he points out that ‘both sides want to use the state to enforce their views on others. One side doesn’t mind using force to expose others to prayer and professing their faith. The other side demands that they have the right to never be offended and demands prohibition of any public expression of faith’. But on the other hand, he point out that ‘most of the conflict between atheists and believers comes up because of public schools. This issue doesn’t exist in private settings such as homes, homeschools, private schools, churches, and art studios, to name a few. In the private sector, every point of view can find a place and these ideas are no threat to others’.

It is no surprise then that Ron Paul is loved by people of all religious or non-religious persuasions – anybody who wants freedom to live their own life and be at peace with others around them. And he is also feared and ridiculed by people of all persuasions – whose insecurities compel them to employ coercion against others by seeking the reins of power.

NOTES

[1] F. A. Hayek, ‘The Intellectuals and Socialism’, in Studies in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics, University of Chicago Press, 1967, p. 194.

[2] Murray Rothbard, For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto, Macmillan Publishing, New York, 1973.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed